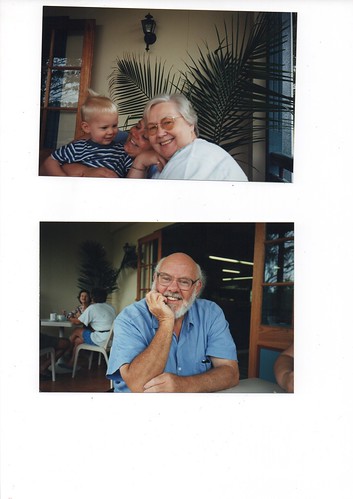

Jean Eileen “Gemma” Chalmers

Jean Eileen Ellison was born in Victoria House in Warrington, Cheshire in 1935. Her grandmother Ruth Bramhall ran Victoria House as a gentleman’s boarding house; she also ran a corner shop. Jean said that Ruth was very much the businesswoman, way ahead of her time.

Ruth’s daughter, Jean’s mother Doris Bramhall, met Jack Ellison at the local church where they both taught Sunday school. Doris and Jack were married in August 1929. They had two daughters, Ruth and Jean.

Jack was an inventor. Jean remembered his workshop full of gadgets, including a haybale-lifter that he sold to a local farmer for a pittance. The farmer registered the design and sold it to Massey Ferguson. “They made a motza out of it,” she said.

During WW2, Doris and Jack ran The Lamb, a traditional English pub in Whitchurch, Shropshire. When the family dog Dandy had puppies with a neighbour’s dog, Monnie, Jean adopted the runt of the litter and named her Victoria Plum. Vicky Plum loved to ride into town in Jean’s bicycle basket.

At school, Jean enjoyed Latin, history and French. She played tennis and got to know another player, Margaret Maidley. Jean described Margaret as very funny, very droll. She and Margaret remained close for the rest of their lives.

Jean won admission to Battersea Domestic Science College in London. At a social night there in 1954 she met a group of men from the neighboring Battersea College. That group included Murray McGrath, who she found delightful, and Robin Chalmers, who she thought was a very pushy Australian. Of Robin, Jean said, “We could talk. With a lot of the people I’d tried to go out with, I had nothing to talk about. Robin chattered away. He was interesting.” Jean loved Robin’s intelligence and how practical he was, how good with his hands.

Jean and Robin were married in Whitchurch in 1961. Jean wore a dress from Brown’s of Cheshire, long-sleeved and short-skirted with a fitted bodice, a Parisian design. Margaret and Ruth were bridesmaids and the best man was Ivor Wong, a friend of Robin’s from college who also remains close to the couple. Jean and Robin honeymooned in the Lake District, visiting the Beatrix Potter museum and Derwent Water.

After the wedding, Jean and Robin lived in a flat on Narbonne Avenue near Clapham Common in London. Robin worked as an electrical engineer and Jean as a comptometer operator. They loved going to jazz clubs to hear Humphrey Littleton, Chris Barber, Johnny Dankworth and Cleo Laine.

When Jean became pregnant, she and Robin moved to a semi-detached house in Shirley. Jean remembered hedgehogs in the garden. Sarah was born in 1965 and Iain followed in 1967. Jean was always very touched at what a doting father Robin was. When they were bringing Sarah home from the hospital, he pulled the car over before they got home. “I have to hold her,” he said. “The nurses wouldn’t let me hold her.” Iain was a home birth, and his dad caught him.

The family sailed to Australia in 1968 on the Fairsky. They saw albatross, dolphins and flying fish. Jean found Cape Town beautiful but was shocked by signs saying For Whites Only and For Blacks Only.

In Sydney, Robin found a job with AWA Two more children followed: Alain in 1969 and Rachel in 1971. With the birth of Rachel the family outgrew their house in West Pymble and moved to the house in Frenchs Forest that would be their home for the next thirty years.

Jean found work at Avon, where she met Hazel Young, the second of her two great friends.

Jean herself was very funny, very droll. She was a working mother – like her Nana, ahead of her time – but she was dedicated to her children and always took their side. When Sarah was diagnosed with epilepsy and when Alain had a badly broken leg, she became their tireless advocate and fought the medical establishment on their behalf.

For a shy, quiet English rose, she had an unexpected spirit of adventure. In 1983 she announced that the entire family would be going away on a hot-air ballooning weekend. It was the first of many such adventures, and quite unforgettable. But daily life in her home was also full of pleasures, like roast Sunday lunches and uproarious games of mah jongg.

In 1990 Sarah married Ian Marrett, whose grandmother lived two doors down from the Frenchs Forest house. Their daughter Kelly was born in 1995 and Ross followed in 1997. In 2000 Rachel married Jeremy Fitzhardinge. They had Claire in 2002 and Julia in 2005. Jean attended the births of all four grandchildren, intrepidly flying solo to San Francisco to help out with Claire and Julia.

After retirement Jean and Robin sold the Frenchs Forest house and bought the Motley, a Winnebago. For seven years they explored Australia, seeing Uluru in the rain, watching whales off the coast of Western Australia. They also flew to Trinidad and Tobago for the wedding of Ivor Wong’s son. They picked up the friendship as if it had never been interrupted. It was the trip of a lifetime.

In 2007 Jean and Robin settled in Barraba, which Robin believes is the most beautiful small town in Australia. Jean quickly became involved with the Clay Pan. Her grandchildren were always plentifully supplied with beautifully knitted cardigans and hats. Jean also made many exquisite pieces of needlework.

Investigation into trouble swallowing in August 2013 showed Jean had aggressive oesophageal cancer. A period in Sydney having radiotherapy treated that cancer, although on January 7 2014 scans showed secondaries.

Jean spent the last four weeks of her life being nursed at Barraba Hospital. The dedicated care and excellent facilities there gave Jean precious time with her husband, sons and daughters and friends. Her great friend Hazel joined with Jean’s daughters in caring for her in Barraba Hospital.

Jean’s sense of humour remained glorious: laughing off concerns about her visitors’ germs, she said: “That won’t kill me!”

Jean is survived by her husband Robin, eldest daughter Sarah, her husband Ian and children Kelly and Ross, eldest son Iain and his partner Rachel, younger son Alain and younger daughter Rachel and her husband Jeremy and daughters Claire and Julia.